Kayla Raden

One by One

By Kayla Raden

The one thing that all humans on this planet have in common is an innate longing to communicate with others. From the moment of birth, we are eager to tell the world “I am here, and I am ready to know you!” Communicating with others and describing things as simple as a blue sky or how you like your morning coffee are things that we do every single day without a second thought. Now, imagine for a second that the letters and words in English that we have grown to love so much have now turned into characters and strokes; imagine a language that not only has characters but is also full of colloquialisms, metaphors, and tones that—as an English speaker—you’ve never had to speak before. I had this experience.

Looking at this seemingly massive collection of characters left me in complete amazement and with a bit of fear.

In the late summer of 2016, I landed in Shanghai, China. I found myself sitting in the back of a taxi in awe, staring at the signs posted for passengers to read. There was not a single word of English. Looking at this seemingly massive collection of characters left me in complete amazement and, to be quite honest, with a bit of fear. My mind began to race, and worries started swirling in my head. How was I to get around if I can’t read street signs? How will I be able to pay my bills? How will I find a bathroom? Will anyone ever be able to understand me?

After a few moments, I caught myself and came back to reality. Staring ahead once again at the sign for taxi passengers, I noticed that some characters looked simpler than others. With my fear beginning to subside, I thought to myself that perhaps 一,二 , and 三 may just be the characters for 1, 2, and 3. I shyly smiled and wrote these characters down in my journal. “Well,” I thought to myself, “Three down, thousands to go!”

Learning Chinese was not much of a necessity during my stay in China. I imagine that I could have gotten by using translating apps and asking my friends for help, but this was not the life I wanted for myself. By not understanding the people around me and not being able to laugh with everyone else in the movie theaters, I felt that I would be missing out on wonderful human interactions.

Studying Chinese with my friends who are native speakers allowed me to understand the language’s beautiful complexity and its historical richness. Slowly, Chinese changed from my second language to something more special – it became another way for me to communicate and express myself. Upon returning to the United States, I felt a longing for all the things I missed about China. I missed the food, the traveling, but most of all I missed the friendships I made with people I met during my travels.

Studying Chinese with my friends who are native speakers allowed me to understand the language’s beautiful complexity and its historical richness. Slowly, Chinese changed from my second language to something more special – it became another way for me to communicate and express myself. Upon returning to the United States, I felt a longing for all the things I missed about China. I missed the food, the traveling, but most of all I missed the friendships I made with people I met during my travels.

Walking into the Confucius Institute at SUNY College of Optometry felt like I was back with my old friends in China. I was greeted with a warm 你好 and a smile. I knew that I had found my piece of Shanghai here at home. Over the course of several months, I studied both independently and with the help of teachers at the Confucius Institute. Looking forward to each visit, I always had new words and phrases that I wanted to practice speaking. Knowing that there was a place where I would always be welcome to practice my Chinese gave me the motivation I needed to really push myself to study harder and go beyond my comfort zone.

A relative asked me why I loved studying Chinese so much. It took me a moment to really think about my answer. “It’s humbling,” I said, “it’s a language completely rooted in its own history and to understand even just a piece of the language is to understand an entire part of world history.” With each character, there is a story and the use of these characters in new and modern ways shows how both versatile and flexible such an ancient language can be.

Learning Chinese has not only taught me about history, but it has taught me about empathy and humility.

Learning Chinese has not only taught me about history, but it has taught me about empathy and humility. Recently, I have also begun to learn Chinese calligraphy and character writing. Painstakingly, I look over each stroke, and I feel like a child learning language for the first time. I am learning how to write my name all over again. Once I was satisfied with the look of my characters, I took a picture of the worksheet and sent it to one of my friends in China. The caption below my large, proud, and hand-written characters said, “How will I ever learn to write all of these?” Without pause, he simply replied, “One by one.”

Kayla Raden

凯拉

Confucius Institute at SUNY College of Optometry

High School Biology and Chemistry Teacher

Marlton, New Jersey

Kayla Raden is a high school biology and chemistry teacher from New Jersey.

Kayla spent a year teaching science at an international high school in Shanghai, China and traveled to several cities in China during her time abroad. While in China, she fell in love with the Chinese language and began to study the characters and learn conversational Chinese from friends. Upon returning to the United States, Kayla joined the Confucius Institute at SUNY College of Optometry and found her Shanghai here at home. She has studied and passed HSK levels 1, 2, and 3 in under 6 months. In the future, Kayla hopes to use her passion for language learning and science to continue teaching students from around the world.

My Confucius Institute Story

My Confucius Institute Story This time it was different.

This time it was different. We beefed up their itinerary to a degree that was difficult to imagine. And yet, no one complained. They were literally immersed in whatever China could offer, and this total immersion was shocking, but not entirely surprising. Because I, too, went through this “immersion” experience when I came to China for the first time. Our students asked us economics-related questions and initiated some serious discussions. They wanted to discuss the economic and social aspects of China during lunch, on a train, and during a walk. They were eager to practice Tai Chi early in a park, to do research on a train to Beijing, and to read articles in China Daily on a bus. We, as teachers, truly appreciated their never-ending curiosity, their unceasing hunger for knowledge and new experiences, and their extraordinary open-mindedness. It made our efforts really worthwhile.

We beefed up their itinerary to a degree that was difficult to imagine. And yet, no one complained. They were literally immersed in whatever China could offer, and this total immersion was shocking, but not entirely surprising. Because I, too, went through this “immersion” experience when I came to China for the first time. Our students asked us economics-related questions and initiated some serious discussions. They wanted to discuss the economic and social aspects of China during lunch, on a train, and during a walk. They were eager to practice Tai Chi early in a park, to do research on a train to Beijing, and to read articles in China Daily on a bus. We, as teachers, truly appreciated their never-ending curiosity, their unceasing hunger for knowledge and new experiences, and their extraordinary open-mindedness. It made our efforts really worthwhile.

Although there have been several languages that sourced from me an utter fascination and the desire to persist in learning, Chinese has residency in the most secure depths of my heart and shall continue to henceforth. Had I not taken up Chinese four years ago, I would have never been able to establish the relationships that I have with hard-working, genuinely kind-hearted teachers, who dedicate their time and energy to tautening their students’ connection to the world’s most-spoken language; and with peers with whom I share a common interest or two. I also realize now, four years later, that, had I not fallen head over heels for this one linguistic miracle, today I would still be an immature, unmotivated adolescent more interested in selecting an ensemble for the following day than a solid career, that will ensure my survival long after graduation. Needless to say, the Mandarin facet of Chinese shaped my life into a meaningful cycle of inspiration, looking to Chinese whenever I need a pick-me-up or a friend that will not disappoint, and convincing myself that I have finally accomplished something worthy of both commendation and awe; mostly, I have been searching for approval from myself.

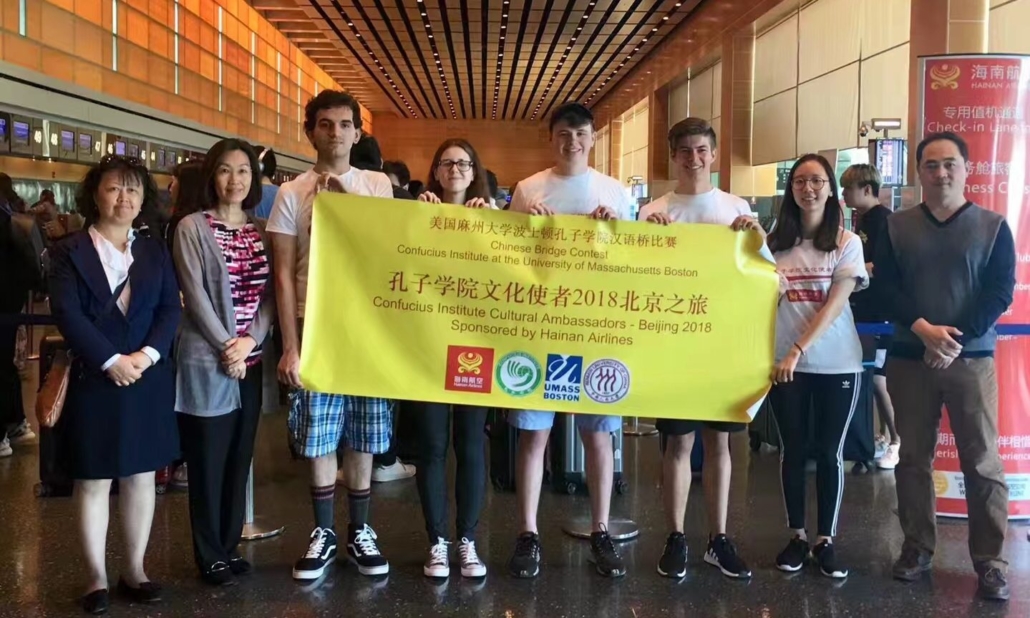

Although there have been several languages that sourced from me an utter fascination and the desire to persist in learning, Chinese has residency in the most secure depths of my heart and shall continue to henceforth. Had I not taken up Chinese four years ago, I would have never been able to establish the relationships that I have with hard-working, genuinely kind-hearted teachers, who dedicate their time and energy to tautening their students’ connection to the world’s most-spoken language; and with peers with whom I share a common interest or two. I also realize now, four years later, that, had I not fallen head over heels for this one linguistic miracle, today I would still be an immature, unmotivated adolescent more interested in selecting an ensemble for the following day than a solid career, that will ensure my survival long after graduation. Needless to say, the Mandarin facet of Chinese shaped my life into a meaningful cycle of inspiration, looking to Chinese whenever I need a pick-me-up or a friend that will not disappoint, and convincing myself that I have finally accomplished something worthy of both commendation and awe; mostly, I have been searching for approval from myself. Participating in the Chinese Bridge Speech Competition, sponsored by UMass’ Confucius Institute, also earned me the ability to travel for the first time to China. All twenty-four finalists were invited to participate in a two-week tour of three of China’s most important cities: Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. This tour was made possible by a language camp organized by the Confucius Institute, which likewise covered the cost of all the food, activities, and lodging we enjoyed when in China. Said trip took place two years ago in July, but I’m as grateful to CI now as I was then for ensuring that two-dozen teens relish a summer abundant in cultural revelations, exposures to the Chinese language, and moments to transform strangers into lifelong friends.

Participating in the Chinese Bridge Speech Competition, sponsored by UMass’ Confucius Institute, also earned me the ability to travel for the first time to China. All twenty-four finalists were invited to participate in a two-week tour of three of China’s most important cities: Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. This tour was made possible by a language camp organized by the Confucius Institute, which likewise covered the cost of all the food, activities, and lodging we enjoyed when in China. Said trip took place two years ago in July, but I’m as grateful to CI now as I was then for ensuring that two-dozen teens relish a summer abundant in cultural revelations, exposures to the Chinese language, and moments to transform strangers into lifelong friends.

The abacus competition came and went way too fast. Besides taking home a second place trophy for his abacus prowess, my son was lauded for making a lengthy speech in Mandarin in front of the 800 contestants, and then another speech the next day in front of over 1,200 attendees, which would later be broadcast on TV. We were invited to the Hanban headquarters, where my good friend and our school partner Dr. Lily Cheng interpreted my English words into Mandarin for other individuals. I was too shy to put to use any of the Mandarin I had learned throughout the year.

The abacus competition came and went way too fast. Besides taking home a second place trophy for his abacus prowess, my son was lauded for making a lengthy speech in Mandarin in front of the 800 contestants, and then another speech the next day in front of over 1,200 attendees, which would later be broadcast on TV. We were invited to the Hanban headquarters, where my good friend and our school partner Dr. Lily Cheng interpreted my English words into Mandarin for other individuals. I was too shy to put to use any of the Mandarin I had learned throughout the year.

In third grade, I entered my first Chinese Competition offered by the Southern California Council of Chinese Schools, where I was awarded the fourth place in the elementary poetry recitation category. Through this award, I helped Riverview Elementary place ahead of our rival school. That same year I competed in my first Chinese Bridge Competition through the Confucius Institute at San Diego State University. Though I did not win, I studied a poem and learned a lot about China through a Chinese poet who was studying in England.

In third grade, I entered my first Chinese Competition offered by the Southern California Council of Chinese Schools, where I was awarded the fourth place in the elementary poetry recitation category. Through this award, I helped Riverview Elementary place ahead of our rival school. That same year I competed in my first Chinese Bridge Competition through the Confucius Institute at San Diego State University. Though I did not win, I studied a poem and learned a lot about China through a Chinese poet who was studying in England.

Beijing Sneakers. The ground these sneakers step upon is o’ so foreign, but o’ so familiar. The air in Beijing so thick, but so real and invigorating. These sneakers fall on uneven stairs, on cobblestone older than China itself. They look beyond a wall and see more beauty and culture than any sneaker had before. They become unlaced as cultures collide and they open themselves to a China that is never described as it should be in history books. A China full of different shoes, of all different sizes, in all kinds of conditions. A China where despite the difference, love is formed through a single greeting, and brotherhood through a single meal. Sneakers tainted by watercolor paint from kite-making with young souls in learning places named after brave warriors.

Beijing Sneakers. The ground these sneakers step upon is o’ so foreign, but o’ so familiar. The air in Beijing so thick, but so real and invigorating. These sneakers fall on uneven stairs, on cobblestone older than China itself. They look beyond a wall and see more beauty and culture than any sneaker had before. They become unlaced as cultures collide and they open themselves to a China that is never described as it should be in history books. A China full of different shoes, of all different sizes, in all kinds of conditions. A China where despite the difference, love is formed through a single greeting, and brotherhood through a single meal. Sneakers tainted by watercolor paint from kite-making with young souls in learning places named after brave warriors. Shanghai Sneakers. Stylish sneakers, enriched by the colliding cultures and endless trade. Sneakers with matching shirts, pants, jewelry, and hats due to the array of shops, small and large, full of goods. Some Arabic, Russian, and Japanese found their way onto these sneakers as all the world’s people collide in one dining place.

Shanghai Sneakers. Stylish sneakers, enriched by the colliding cultures and endless trade. Sneakers with matching shirts, pants, jewelry, and hats due to the array of shops, small and large, full of goods. Some Arabic, Russian, and Japanese found their way onto these sneakers as all the world’s people collide in one dining place.

Perhaps the most influential piece in my journey was my Chinese teacher, Lou Laoshi. She began teaching me in my freshman year of high school, yet another nervous start in my educational endeavors. While I was anxious about taking such a difficult language, Lou Laoshi made it approachable. I recall grumbling about her strict policies: we were only to speak Chinese in the classroom, and we were to memorize characters religiously. These practices soon bloomed into a wonderful foundation, allowing me to climb my way up to the top of my class. I even began speaking Chinese to my family, much to their dismay. I still accidentally thank waiters in the language! Even though I didn’t realize it, I was immersing myself in Chinese, inside and outside of the classroom. I began to drink Chinese tea and research Chinese ways of life, which helped me navigate my own struggles throughout high school. We even had the chance to put on a play in Chinese for the entire school, entitled “Butterfly Lovers.” I have never been very outgoing, but this play created the perfect opportunity for me to get out of my cocoon. We spent weeks practicing the lines in Chinese, giving me the chance to learn even more words and phrases while using them to talk with my classmates. Lou Laoshi pushed me to practice the language and pushed me to be confident on stage. It worked! Despite my racked nerves, the play was a success. Not only did it advance my language learning, it also brought me out of my shell and allowed me to share my passion for Chinese with the whole school. Without Lou Laoshi pushing me and my classmates to succeed, this dream for my class would never have blossomed into reality.

Perhaps the most influential piece in my journey was my Chinese teacher, Lou Laoshi. She began teaching me in my freshman year of high school, yet another nervous start in my educational endeavors. While I was anxious about taking such a difficult language, Lou Laoshi made it approachable. I recall grumbling about her strict policies: we were only to speak Chinese in the classroom, and we were to memorize characters religiously. These practices soon bloomed into a wonderful foundation, allowing me to climb my way up to the top of my class. I even began speaking Chinese to my family, much to their dismay. I still accidentally thank waiters in the language! Even though I didn’t realize it, I was immersing myself in Chinese, inside and outside of the classroom. I began to drink Chinese tea and research Chinese ways of life, which helped me navigate my own struggles throughout high school. We even had the chance to put on a play in Chinese for the entire school, entitled “Butterfly Lovers.” I have never been very outgoing, but this play created the perfect opportunity for me to get out of my cocoon. We spent weeks practicing the lines in Chinese, giving me the chance to learn even more words and phrases while using them to talk with my classmates. Lou Laoshi pushed me to practice the language and pushed me to be confident on stage. It worked! Despite my racked nerves, the play was a success. Not only did it advance my language learning, it also brought me out of my shell and allowed me to share my passion for Chinese with the whole school. Without Lou Laoshi pushing me and my classmates to succeed, this dream for my class would never have blossomed into reality. Chinese, with all its complications and variations, is a language that I will never forget. My experience learning Chinese has been immensely satisfying and life-changing. Many of my memories are tied to it – the class, the tones, even the characters. One of the first striking things that I remember learning about Chinese was that the character for home and family were the same: 家 (pronounced jiā). That is exactly what I found in the Chinese language; not only a family with my fellow students, but also a second home. Though the language’s birthplace is halfway across the globe, it will always have a piece of my North Carolina heart.

Chinese, with all its complications and variations, is a language that I will never forget. My experience learning Chinese has been immensely satisfying and life-changing. Many of my memories are tied to it – the class, the tones, even the characters. One of the first striking things that I remember learning about Chinese was that the character for home and family were the same: 家 (pronounced jiā). That is exactly what I found in the Chinese language; not only a family with my fellow students, but also a second home. Though the language’s birthplace is halfway across the globe, it will always have a piece of my North Carolina heart.

For a few weeks, before we left, I started learning to speak Chinese. Luckily my library had an MP3 course in Mandarin, otherwise, I may have learned Cantonese instead. I completed 15 half hour lessons before we left for China. While in China, I found it a little difficult communicating in Chinese with my limited vocabulary. Luckily, I rarely had to rely on my minimal Mandarin speaking skills, as the Chinese people and I usually innovated some means of communication. Whenever we were unsure of our path, inevitably a kind stranger directed us on our journey, usually in English, but always understood.

For a few weeks, before we left, I started learning to speak Chinese. Luckily my library had an MP3 course in Mandarin, otherwise, I may have learned Cantonese instead. I completed 15 half hour lessons before we left for China. While in China, I found it a little difficult communicating in Chinese with my limited vocabulary. Luckily, I rarely had to rely on my minimal Mandarin speaking skills, as the Chinese people and I usually innovated some means of communication. Whenever we were unsure of our path, inevitably a kind stranger directed us on our journey, usually in English, but always understood. My Hongkongese mother started me off on my Chinese learning path by teaching me Cantonese from childhood. One of my first foreign language fumbles happened when I was a toddler. I still hear about this story today—my mother chuckles when she describes how difficult it was to teach me how to say “bone” in Cantonese, pronounced gwat. Somehow my imitation came out as “brat.” She would tell me the proper way of saying “bone” each day until I could pronounce it. I never would have guessed that this was simply the beginning to my interest in foreign language. Fast-forward a decade, Cantonese had taken a special place in my life—it is not only my roots and memories but also my connection to my Hong Kong family.

My Hongkongese mother started me off on my Chinese learning path by teaching me Cantonese from childhood. One of my first foreign language fumbles happened when I was a toddler. I still hear about this story today—my mother chuckles when she describes how difficult it was to teach me how to say “bone” in Cantonese, pronounced gwat. Somehow my imitation came out as “brat.” She would tell me the proper way of saying “bone” each day until I could pronounce it. I never would have guessed that this was simply the beginning to my interest in foreign language. Fast-forward a decade, Cantonese had taken a special place in my life—it is not only my roots and memories but also my connection to my Hong Kong family.

So, entering college as a student of Russian (as well as French and Spanish), I resolved to take up the study of Mandarin. But my small college in Maine offered no courses in that language. Following graduation from college, undeterred, I enrolled in an evening course in Mandarin at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education near Harvard University, and thus launched a haphazard, often frustrating trajectory in the study of Chinese. That journey wound through George Washington and Georgetown universities, the State Department’s Foreign Language Institute’s early morning classes … then, after a 15-year hiatus, resumed in intensive tutoring classes in 1999 and later in independent study at George Mason University. If I had not learned to speak Chinese as fluently as I could in Western languages, at least I had taught myself to read Chinese, plowing through several longish 20th-century novels by such authors as Lu Xun, Ba Jin, Lao She, Shen Congwen, and Yu Hua.

So, entering college as a student of Russian (as well as French and Spanish), I resolved to take up the study of Mandarin. But my small college in Maine offered no courses in that language. Following graduation from college, undeterred, I enrolled in an evening course in Mandarin at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education near Harvard University, and thus launched a haphazard, often frustrating trajectory in the study of Chinese. That journey wound through George Washington and Georgetown universities, the State Department’s Foreign Language Institute’s early morning classes … then, after a 15-year hiatus, resumed in intensive tutoring classes in 1999 and later in independent study at George Mason University. If I had not learned to speak Chinese as fluently as I could in Western languages, at least I had taught myself to read Chinese, plowing through several longish 20th-century novels by such authors as Lu Xun, Ba Jin, Lao She, Shen Congwen, and Yu Hua. In 2012, I retired from the Department of State, winding up a 37-year-long career in government. Reflecting that I should find some way to show appreciation for the Confucius Institute’s generosity towards our family, I began to attend weekly presentations about Chinese affairs sponsored by George Mason’s Confucius Institute. By late 2014, this casual contact had led to the formation of a Chinese Reading Club at George Mason’s Confucius Institute, which by mid-2016 boasted of six experienced Chinese learners who could read and discuss difficult, highly literary shorter works of such esteemed Chinese authors as Mo Yan, Liu Zhenyun, Bi Feiyu and Su Tong. We suspect that this advanced Chinese Reading Group – whose members are not native speakers – may be unique within the United States. The challenges and joys (!) of our biweekly group meetings to decipher the cultural, linguistic and literary secrets of the short stories we read, in Chinese, under the expert guidance of our CI teachers He Xiao and Wang Lihong. have brought us to a deeper understanding of China and the Chinese mind through modern literature – even to those in our group who have lived and studied China and Chinese for decades.

In 2012, I retired from the Department of State, winding up a 37-year-long career in government. Reflecting that I should find some way to show appreciation for the Confucius Institute’s generosity towards our family, I began to attend weekly presentations about Chinese affairs sponsored by George Mason’s Confucius Institute. By late 2014, this casual contact had led to the formation of a Chinese Reading Club at George Mason’s Confucius Institute, which by mid-2016 boasted of six experienced Chinese learners who could read and discuss difficult, highly literary shorter works of such esteemed Chinese authors as Mo Yan, Liu Zhenyun, Bi Feiyu and Su Tong. We suspect that this advanced Chinese Reading Group – whose members are not native speakers – may be unique within the United States. The challenges and joys (!) of our biweekly group meetings to decipher the cultural, linguistic and literary secrets of the short stories we read, in Chinese, under the expert guidance of our CI teachers He Xiao and Wang Lihong. have brought us to a deeper understanding of China and the Chinese mind through modern literature – even to those in our group who have lived and studied China and Chinese for decades.