Amelia AiYan Engstrom

My Mandarin Journey

By Amelia AiYan Engstrom

I was born in Fuling, China. Chinese was the only language I knew. Twelve months after I was born, I was adopted by two Americans who spoke a language that was foreign. They brought me back to America where their language became familiar to me.

I was born in Fuling, China. Chinese was the only language I knew. Twelve months after I was born, I was adopted by two Americans who spoke a language that was foreign. They brought me back to America where their language became familiar to me.

Four years later, I was a timid kindergartener sitting at a small desk waiting patiently for class to start. I was unaware that the class I was about to attend would be life-changing. As the teacher began to speak, I started to hear words that were alien, but beautiful. It was like hearing spoken music. I soon found out that those strange words are part of a language called Mandarin Chinese. That was the spark that ignited the blazing passion I have for Chinese. As time went on, I learned more about the language itself as well as Chinese culture.

I vividly remember my first Moon Festival. I sat on a blanket on the wet grass in my mother’s lap surrounded by my family and many school friends. The erhu was being played in the background as we all ate mooncakes, watched the moon rise, and enjoyed each other’s presence. Children danced around with glow sticks and waved homemade lanterns. The night would have been pitch black if not for the shining beacon that was the moon. My kindergarten class had just finished performing a song about the Moon Festival that was composed by our teacher. That night was not just about lanterns and festivities, but about the importance of family.

Since I attended a Mandarin immersion program in a Confucius Classroom, I had the opportunity to increase my skills and knowledge every day. I looked forward to learning more about Chinese culture. My favorite parts were baking mooncakes, making dumplings, and folding origami.

When I was in third grade, our class wanted to do something big for Chinese New Year. We decided to do a presentation in front of the whole school. It would have music, dancing, and, most importantly, dragons! There would be two different dragons, one for each side of the auditorium. They would start in the very back row and snake their way through the aisles up onto the stage. I was a shy, quiet kid, but I was chosen to be the head of the dragon. The head of the dragon needs to be exciting; the performer shakes the head in people’s faces and moves up and down. The head leads the rest of the body. This was an experience of a lifetime. I had a blast learning how to move the dragon around. Not only did I have fun and learn more about Chinese culture, but it also forced me to leave my comfort zone and be a leader.

I switched to a different school for junior high and with the new school came a new Confucius Classroom. My new teacher took us to Chinatown in San Francisco for the annual New Year’s Parade. It was amazing to experience the culture in person instead of from a textbook. We were sent into Chinatown with a list of things to find for a scavenger hunt. This gave us a reason to talk to the street shop owners and use our language skills. The town was decorated festively with lanterns and even a statue of Monkey King (孙悟空). I especially liked throwing poppers on the ground and surprising everyone around me. We also toured the Asian Art Museum and expanded our knowledge of Chinese art. When it came time for the parade, my classmates and I sat enthusiastically on the edge of the sidewalk munching on goodies we had just bought in Chinatown. The parade was great! All the floats were lavishly adorned, the bands played fun songs, and the firecrackers were a bundle of exhilaration. Not only has Chinese class been my passion, but it has also opened doors to new adventures.

I switched to a different school for junior high and with the new school came a new Confucius Classroom. My new teacher took us to Chinatown in San Francisco for the annual New Year’s Parade. It was amazing to experience the culture in person instead of from a textbook. We were sent into Chinatown with a list of things to find for a scavenger hunt. This gave us a reason to talk to the street shop owners and use our language skills. The town was decorated festively with lanterns and even a statue of Monkey King (孙悟空). I especially liked throwing poppers on the ground and surprising everyone around me. We also toured the Asian Art Museum and expanded our knowledge of Chinese art. When it came time for the parade, my classmates and I sat enthusiastically on the edge of the sidewalk munching on goodies we had just bought in Chinatown. The parade was great! All the floats were lavishly adorned, the bands played fun songs, and the firecrackers were a bundle of exhilaration. Not only has Chinese class been my passion, but it has also opened doors to new adventures.

As time went on, my Chinese journey began to feel like a roller coaster. Sometimes I would be at the peak, fully immersed in the culture and loving life. I would race to class ready to learn about the culture of my past. Other times I would be at the bottom of a hill. I would be mad at my parents for making me take such a difficult language. But, at the end of the day, I have always come back around. Mandarin has been a part of my life for so long that I am not sure what I would do without it. It has not only taught me about other cultures but also about core values like perseverance, hard work, and leadership. Mandarin Chinese has connected me with my past, improved my present, and paved the way for my future.

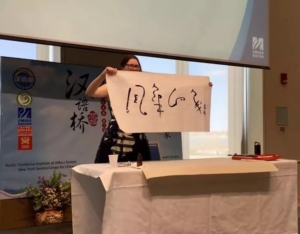

As a junior in Mandarin IV, my class has the highest level of proficiency in the school. Because of this, we were responsible for producing our school’s performance for the festival. My teacher gave me the privilege of coming up with the concept and theme, along with directing our play. I was extremely excited because the Confucius Festival is how all the Chinese classes in the Cleveland area see what other students are learning and it gave my Chinese-learning friends from other schools the opportunity to see my work on stage. Because my classmates and I collectively love the music from the 2008 Beijing Olympics, I decided we would recreate that moment on stage. We all represented different athletes and performed a closing ceremony skit where students gave speeches, showed off Olympic medals, sang and danced— all in Chinese.

As a junior in Mandarin IV, my class has the highest level of proficiency in the school. Because of this, we were responsible for producing our school’s performance for the festival. My teacher gave me the privilege of coming up with the concept and theme, along with directing our play. I was extremely excited because the Confucius Festival is how all the Chinese classes in the Cleveland area see what other students are learning and it gave my Chinese-learning friends from other schools the opportunity to see my work on stage. Because my classmates and I collectively love the music from the 2008 Beijing Olympics, I decided we would recreate that moment on stage. We all represented different athletes and performed a closing ceremony skit where students gave speeches, showed off Olympic medals, sang and danced— all in Chinese. I remember when I was 11 years old at my first Confucius Festival and I did not have the language proficiency to comprehend most of the dialogue and jokes or the cultural awareness to recognize any of the stories and songs. I can look back on that moment and compare it to now as I perform skits in Mandarin, talk to Chinese students about jokes that do not quite translate to English and talk to my friends about our favorite Chinese songs and foods. Each October it is nice to go down to Cleveland State and see how much more information I can ascertain. I was excited this year because I recognized a lot of the stories the elementary students acted out. Most notably, a group of children acted out the race to determine the 12 Chinese zodiac animals and I remember translating that story into English in my class.

I remember when I was 11 years old at my first Confucius Festival and I did not have the language proficiency to comprehend most of the dialogue and jokes or the cultural awareness to recognize any of the stories and songs. I can look back on that moment and compare it to now as I perform skits in Mandarin, talk to Chinese students about jokes that do not quite translate to English and talk to my friends about our favorite Chinese songs and foods. Each October it is nice to go down to Cleveland State and see how much more information I can ascertain. I was excited this year because I recognized a lot of the stories the elementary students acted out. Most notably, a group of children acted out the race to determine the 12 Chinese zodiac animals and I remember translating that story into English in my class.

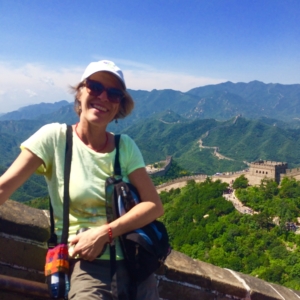

Once I joined the Confucius family, my daily life seemed to always involve China, the Chinese culture, or the Chinese language in some way. Every book I suggested to my book club, fiction or non-fiction, was set in Asia. I decorated my entrance-way with Chinese artifacts, listened to music from Chinese CDs that I had brought back from my trips, and pulled out my 旗袍 qipao for every fancy event that I attended. I also decided to intertwine my cultural work at the German Goethe-Institut with my new knowledge of China. I became part of the “Trialogue” project and a poetry event named “Time Shadows,” in which we presented poems in German, English and Chinese. I became a moderator at the Euro-Asia film festivals in Washington, DC, where I discussed German and Chinese short films together with my Confucius colleagues and friends. I was invited to Michelle Obama’s “100,000 Strong Initiative” talk, the 2012 National Chinese Language Conference in Washington, DC, cultural workshops to learn Chinese calligraphy and how to play mahjong, lessons on using “WeChat” to stay in touch with my Confucius friends, and even my teacher’s apartment to make 饺子 jiao zi.

Once I joined the Confucius family, my daily life seemed to always involve China, the Chinese culture, or the Chinese language in some way. Every book I suggested to my book club, fiction or non-fiction, was set in Asia. I decorated my entrance-way with Chinese artifacts, listened to music from Chinese CDs that I had brought back from my trips, and pulled out my 旗袍 qipao for every fancy event that I attended. I also decided to intertwine my cultural work at the German Goethe-Institut with my new knowledge of China. I became part of the “Trialogue” project and a poetry event named “Time Shadows,” in which we presented poems in German, English and Chinese. I became a moderator at the Euro-Asia film festivals in Washington, DC, where I discussed German and Chinese short films together with my Confucius colleagues and friends. I was invited to Michelle Obama’s “100,000 Strong Initiative” talk, the 2012 National Chinese Language Conference in Washington, DC, cultural workshops to learn Chinese calligraphy and how to play mahjong, lessons on using “WeChat” to stay in touch with my Confucius friends, and even my teacher’s apartment to make 饺子 jiao zi.

At first, I was excited about the prospect; then I considered the challenge and commitment that was necessary to learn a new language and whether I was really up to the task. My actual engagement with the Confucius Institute began in January 2018.

At first, I was excited about the prospect; then I considered the challenge and commitment that was necessary to learn a new language and whether I was really up to the task. My actual engagement with the Confucius Institute began in January 2018. During the program, I saw a CI student who had only nine classes stand on stage in front of nearly two hundred people, and recite a simple poem in Mandarin before a largely Chinese audience. Two other CI students performed a song. What encouragement and motivation!

During the program, I saw a CI student who had only nine classes stand on stage in front of nearly two hundred people, and recite a simple poem in Mandarin before a largely Chinese audience. Two other CI students performed a song. What encouragement and motivation!

The school year was closing to an end, and our teacher told us that she would not be coming back next year. She said our new teacher was coming from China! For me, this was a shock because I did not join Chinese to just learn some pinyin and receive class credit. I was there because I knew I was never going to understand English, even if it was my own language. I had a chance with Chinese to really understand a language and thrive. I was told I was good at grammar and sentence structure, I was so happy to get commended for it. I had never been told in any of my English classes, or other classes, that I was good at English. Though in my Chinese classes, my teacher was so surprised at how well I was getting the language. I was starting to regain hope for myself that I had lost way back in elementary school and this hope I found in Chinese.

The school year was closing to an end, and our teacher told us that she would not be coming back next year. She said our new teacher was coming from China! For me, this was a shock because I did not join Chinese to just learn some pinyin and receive class credit. I was there because I knew I was never going to understand English, even if it was my own language. I had a chance with Chinese to really understand a language and thrive. I was told I was good at grammar and sentence structure, I was so happy to get commended for it. I had never been told in any of my English classes, or other classes, that I was good at English. Though in my Chinese classes, my teacher was so surprised at how well I was getting the language. I was starting to regain hope for myself that I had lost way back in elementary school and this hope I found in Chinese.

Studying Chinese with my friends who are native speakers allowed me to understand the language’s beautiful complexity and its historical richness. Slowly, Chinese changed from my second language to something more special – it became another way for me to communicate and express myself. Upon returning to the United States, I felt a longing for all the things I missed about China. I missed the food, the traveling, but most of all I missed the friendships I made with people I met during my travels.

Studying Chinese with my friends who are native speakers allowed me to understand the language’s beautiful complexity and its historical richness. Slowly, Chinese changed from my second language to something more special – it became another way for me to communicate and express myself. Upon returning to the United States, I felt a longing for all the things I missed about China. I missed the food, the traveling, but most of all I missed the friendships I made with people I met during my travels. My Confucius Institute Story

My Confucius Institute Story This time it was different.

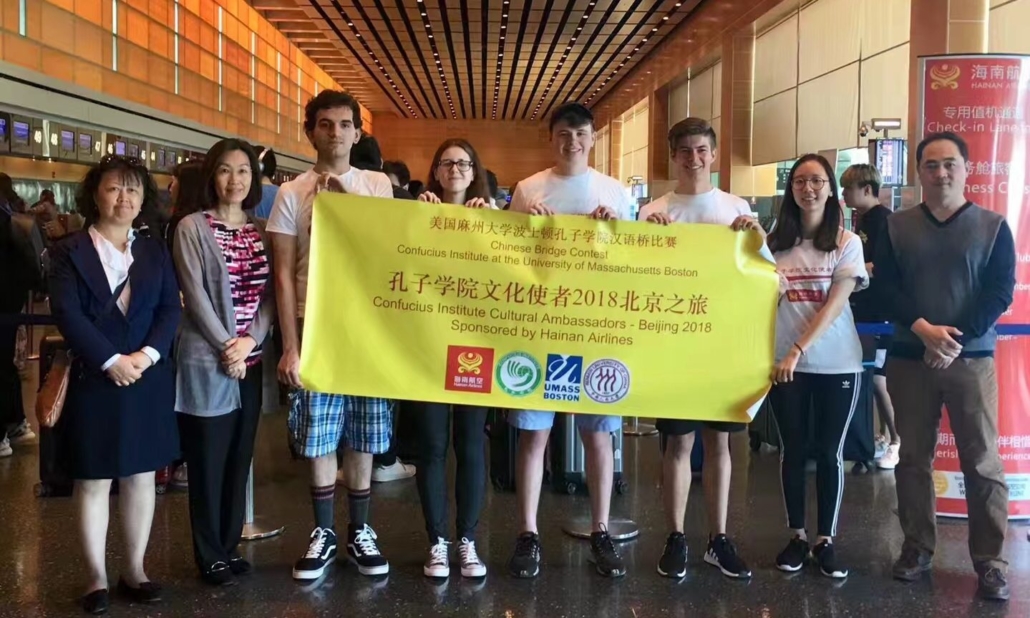

This time it was different. We beefed up their itinerary to a degree that was difficult to imagine. And yet, no one complained. They were literally immersed in whatever China could offer, and this total immersion was shocking, but not entirely surprising. Because I, too, went through this “immersion” experience when I came to China for the first time. Our students asked us economics-related questions and initiated some serious discussions. They wanted to discuss the economic and social aspects of China during lunch, on a train, and during a walk. They were eager to practice Tai Chi early in a park, to do research on a train to Beijing, and to read articles in China Daily on a bus. We, as teachers, truly appreciated their never-ending curiosity, their unceasing hunger for knowledge and new experiences, and their extraordinary open-mindedness. It made our efforts really worthwhile.

We beefed up their itinerary to a degree that was difficult to imagine. And yet, no one complained. They were literally immersed in whatever China could offer, and this total immersion was shocking, but not entirely surprising. Because I, too, went through this “immersion” experience when I came to China for the first time. Our students asked us economics-related questions and initiated some serious discussions. They wanted to discuss the economic and social aspects of China during lunch, on a train, and during a walk. They were eager to practice Tai Chi early in a park, to do research on a train to Beijing, and to read articles in China Daily on a bus. We, as teachers, truly appreciated their never-ending curiosity, their unceasing hunger for knowledge and new experiences, and their extraordinary open-mindedness. It made our efforts really worthwhile.

Although there have been several languages that sourced from me an utter fascination and the desire to persist in learning, Chinese has residency in the most secure depths of my heart and shall continue to henceforth. Had I not taken up Chinese four years ago, I would have never been able to establish the relationships that I have with hard-working, genuinely kind-hearted teachers, who dedicate their time and energy to tautening their students’ connection to the world’s most-spoken language; and with peers with whom I share a common interest or two. I also realize now, four years later, that, had I not fallen head over heels for this one linguistic miracle, today I would still be an immature, unmotivated adolescent more interested in selecting an ensemble for the following day than a solid career, that will ensure my survival long after graduation. Needless to say, the Mandarin facet of Chinese shaped my life into a meaningful cycle of inspiration, looking to Chinese whenever I need a pick-me-up or a friend that will not disappoint, and convincing myself that I have finally accomplished something worthy of both commendation and awe; mostly, I have been searching for approval from myself.

Although there have been several languages that sourced from me an utter fascination and the desire to persist in learning, Chinese has residency in the most secure depths of my heart and shall continue to henceforth. Had I not taken up Chinese four years ago, I would have never been able to establish the relationships that I have with hard-working, genuinely kind-hearted teachers, who dedicate their time and energy to tautening their students’ connection to the world’s most-spoken language; and with peers with whom I share a common interest or two. I also realize now, four years later, that, had I not fallen head over heels for this one linguistic miracle, today I would still be an immature, unmotivated adolescent more interested in selecting an ensemble for the following day than a solid career, that will ensure my survival long after graduation. Needless to say, the Mandarin facet of Chinese shaped my life into a meaningful cycle of inspiration, looking to Chinese whenever I need a pick-me-up or a friend that will not disappoint, and convincing myself that I have finally accomplished something worthy of both commendation and awe; mostly, I have been searching for approval from myself. Participating in the Chinese Bridge Speech Competition, sponsored by UMass’ Confucius Institute, also earned me the ability to travel for the first time to China. All twenty-four finalists were invited to participate in a two-week tour of three of China’s most important cities: Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. This tour was made possible by a language camp organized by the Confucius Institute, which likewise covered the cost of all the food, activities, and lodging we enjoyed when in China. Said trip took place two years ago in July, but I’m as grateful to CI now as I was then for ensuring that two-dozen teens relish a summer abundant in cultural revelations, exposures to the Chinese language, and moments to transform strangers into lifelong friends.

Participating in the Chinese Bridge Speech Competition, sponsored by UMass’ Confucius Institute, also earned me the ability to travel for the first time to China. All twenty-four finalists were invited to participate in a two-week tour of three of China’s most important cities: Beijing, Shanghai, and Hangzhou. This tour was made possible by a language camp organized by the Confucius Institute, which likewise covered the cost of all the food, activities, and lodging we enjoyed when in China. Said trip took place two years ago in July, but I’m as grateful to CI now as I was then for ensuring that two-dozen teens relish a summer abundant in cultural revelations, exposures to the Chinese language, and moments to transform strangers into lifelong friends.

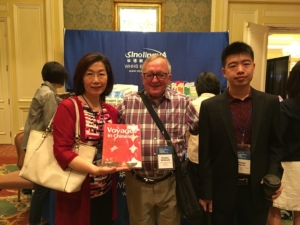

The abacus competition came and went way too fast. Besides taking home a second place trophy for his abacus prowess, my son was lauded for making a lengthy speech in Mandarin in front of the 800 contestants, and then another speech the next day in front of over 1,200 attendees, which would later be broadcast on TV. We were invited to the Hanban headquarters, where my good friend and our school partner Dr. Lily Cheng interpreted my English words into Mandarin for other individuals. I was too shy to put to use any of the Mandarin I had learned throughout the year.

The abacus competition came and went way too fast. Besides taking home a second place trophy for his abacus prowess, my son was lauded for making a lengthy speech in Mandarin in front of the 800 contestants, and then another speech the next day in front of over 1,200 attendees, which would later be broadcast on TV. We were invited to the Hanban headquarters, where my good friend and our school partner Dr. Lily Cheng interpreted my English words into Mandarin for other individuals. I was too shy to put to use any of the Mandarin I had learned throughout the year.

Perhaps the most influential piece in my journey was my Chinese teacher, Lou Laoshi. She began teaching me in my freshman year of high school, yet another nervous start in my educational endeavors. While I was anxious about taking such a difficult language, Lou Laoshi made it approachable. I recall grumbling about her strict policies: we were only to speak Chinese in the classroom, and we were to memorize characters religiously. These practices soon bloomed into a wonderful foundation, allowing me to climb my way up to the top of my class. I even began speaking Chinese to my family, much to their dismay. I still accidentally thank waiters in the language! Even though I didn’t realize it, I was immersing myself in Chinese, inside and outside of the classroom. I began to drink Chinese tea and research Chinese ways of life, which helped me navigate my own struggles throughout high school. We even had the chance to put on a play in Chinese for the entire school, entitled “Butterfly Lovers.” I have never been very outgoing, but this play created the perfect opportunity for me to get out of my cocoon. We spent weeks practicing the lines in Chinese, giving me the chance to learn even more words and phrases while using them to talk with my classmates. Lou Laoshi pushed me to practice the language and pushed me to be confident on stage. It worked! Despite my racked nerves, the play was a success. Not only did it advance my language learning, it also brought me out of my shell and allowed me to share my passion for Chinese with the whole school. Without Lou Laoshi pushing me and my classmates to succeed, this dream for my class would never have blossomed into reality.

Perhaps the most influential piece in my journey was my Chinese teacher, Lou Laoshi. She began teaching me in my freshman year of high school, yet another nervous start in my educational endeavors. While I was anxious about taking such a difficult language, Lou Laoshi made it approachable. I recall grumbling about her strict policies: we were only to speak Chinese in the classroom, and we were to memorize characters religiously. These practices soon bloomed into a wonderful foundation, allowing me to climb my way up to the top of my class. I even began speaking Chinese to my family, much to their dismay. I still accidentally thank waiters in the language! Even though I didn’t realize it, I was immersing myself in Chinese, inside and outside of the classroom. I began to drink Chinese tea and research Chinese ways of life, which helped me navigate my own struggles throughout high school. We even had the chance to put on a play in Chinese for the entire school, entitled “Butterfly Lovers.” I have never been very outgoing, but this play created the perfect opportunity for me to get out of my cocoon. We spent weeks practicing the lines in Chinese, giving me the chance to learn even more words and phrases while using them to talk with my classmates. Lou Laoshi pushed me to practice the language and pushed me to be confident on stage. It worked! Despite my racked nerves, the play was a success. Not only did it advance my language learning, it also brought me out of my shell and allowed me to share my passion for Chinese with the whole school. Without Lou Laoshi pushing me and my classmates to succeed, this dream for my class would never have blossomed into reality. Chinese, with all its complications and variations, is a language that I will never forget. My experience learning Chinese has been immensely satisfying and life-changing. Many of my memories are tied to it – the class, the tones, even the characters. One of the first striking things that I remember learning about Chinese was that the character for home and family were the same: 家 (pronounced jiā). That is exactly what I found in the Chinese language; not only a family with my fellow students, but also a second home. Though the language’s birthplace is halfway across the globe, it will always have a piece of my North Carolina heart.

Chinese, with all its complications and variations, is a language that I will never forget. My experience learning Chinese has been immensely satisfying and life-changing. Many of my memories are tied to it – the class, the tones, even the characters. One of the first striking things that I remember learning about Chinese was that the character for home and family were the same: 家 (pronounced jiā). That is exactly what I found in the Chinese language; not only a family with my fellow students, but also a second home. Though the language’s birthplace is halfway across the globe, it will always have a piece of my North Carolina heart.